The Los Angeles Dingbat Apartment

The Hauser dingbat apartment[James Black]

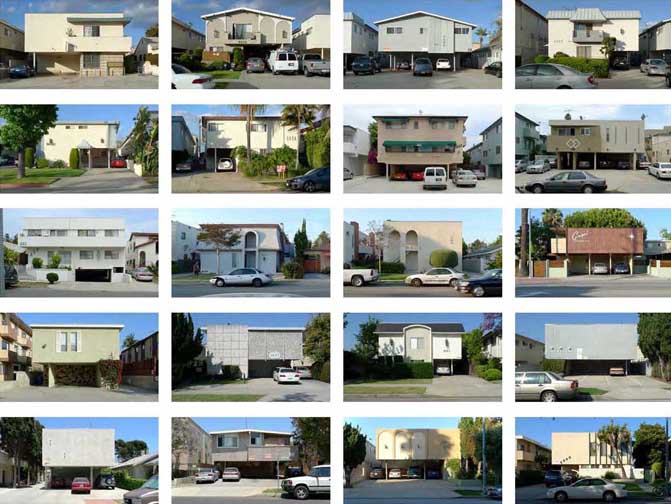

The dingbat apartment blankets the urbanized flatlands of Southern California like the chaparral covering the surrounding rugged hills and valleys. Emerging in the early 1950s this new native species of apartment structures found its niche in the building boom of the late ’50s and ’60s and quickly spread across the fertile expanse of postwar Los Angeles and the American Southwest. The dingbat easily insinuated itself into Los Angeles’ expansive grid of single-family residences, replacing individual homes and taking over entire neighborhoods, subtly, yet profoundly transforming the landscape of the city.

Dingbat Grid [James Black]

The dingbat is usually a two-story walk-up built of stucco over wood framing with an often extravagantly dolled-up facade—Mansard, Tiki, Mod, anything fantastic or exotic. However, its impact on the built and cultural context of Los Angeles is much more complex and nuanced than the simple structure might suggest.

Aerial view of dingbat neighborhood in West Los Angeles

The dingbat is the quintessential Los Angeles apartment building—inhabited by hundreds of thousands of Angelenos who, despite the catchy script on the facade, never realized their apartment type had a name. The dingbat is also quintessentially Los Angeles in its contradictions: provisional yet persistent, pretentious yet mundane, eclectic yet generic, and an agent of both urban density and sprawl.

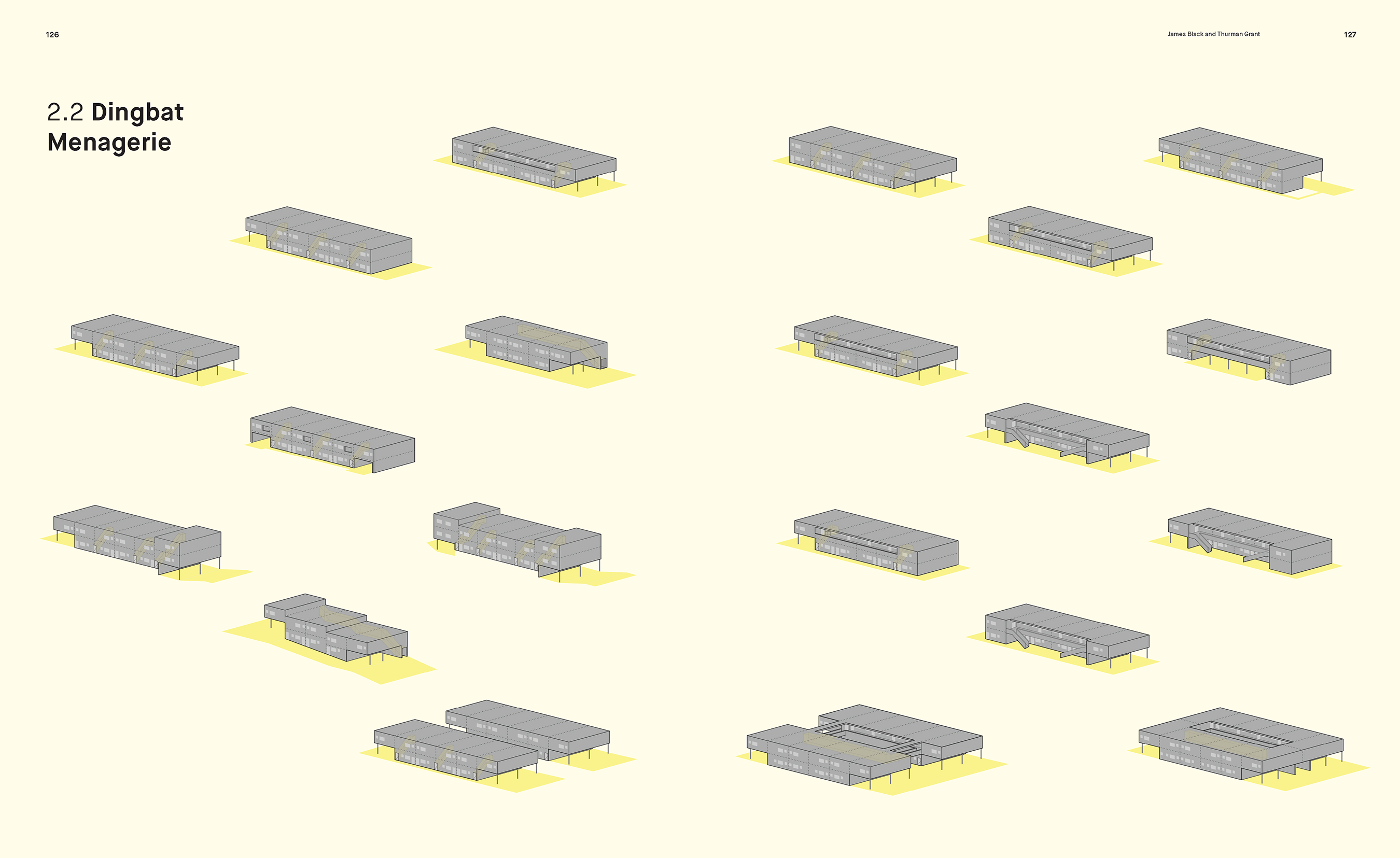

Dingbat Menagerie [Thurman Grant]: Drawings of various sub-types of dingbat apartments, from “Field Guide to Dingbats,” featured in Dingbat 2.0.

The dingbat, while a product of the ’50s and ’60s, is so

firmly rooted in the ethos of the city that it remains relevant in looking

toward the city’s future. Given the degree to which Los Angeles’ development

influenced or predicted a global trend in decentralized urban growth, the

city’s efforts to densify may well hold valuable lessons for the role that

housing plays in the current international wave of city-making, including

determining the ideal scale for the grain of new development and questioning

the role of the vernacular, the generic, the popular, and the populist.

Dingbat Menagerie [Thurman Grant]: Drawings of various sub-types of dingbat apartments, from “Field Guide to Dingbats,” featured in Dingbat 2.0.

The dingbat, while a product of the ’50s and ’60s, is so

firmly rooted in the ethos of the city that it remains relevant in looking

toward the city’s future. Given the degree to which Los Angeles’ development

influenced or predicted a global trend in decentralized urban growth, the

city’s efforts to densify may well hold valuable lessons for the role that

housing plays in the current international wave of city-making, including

determining the ideal scale for the grain of new development and questioning

the role of the vernacular, the generic, the popular, and the populist.

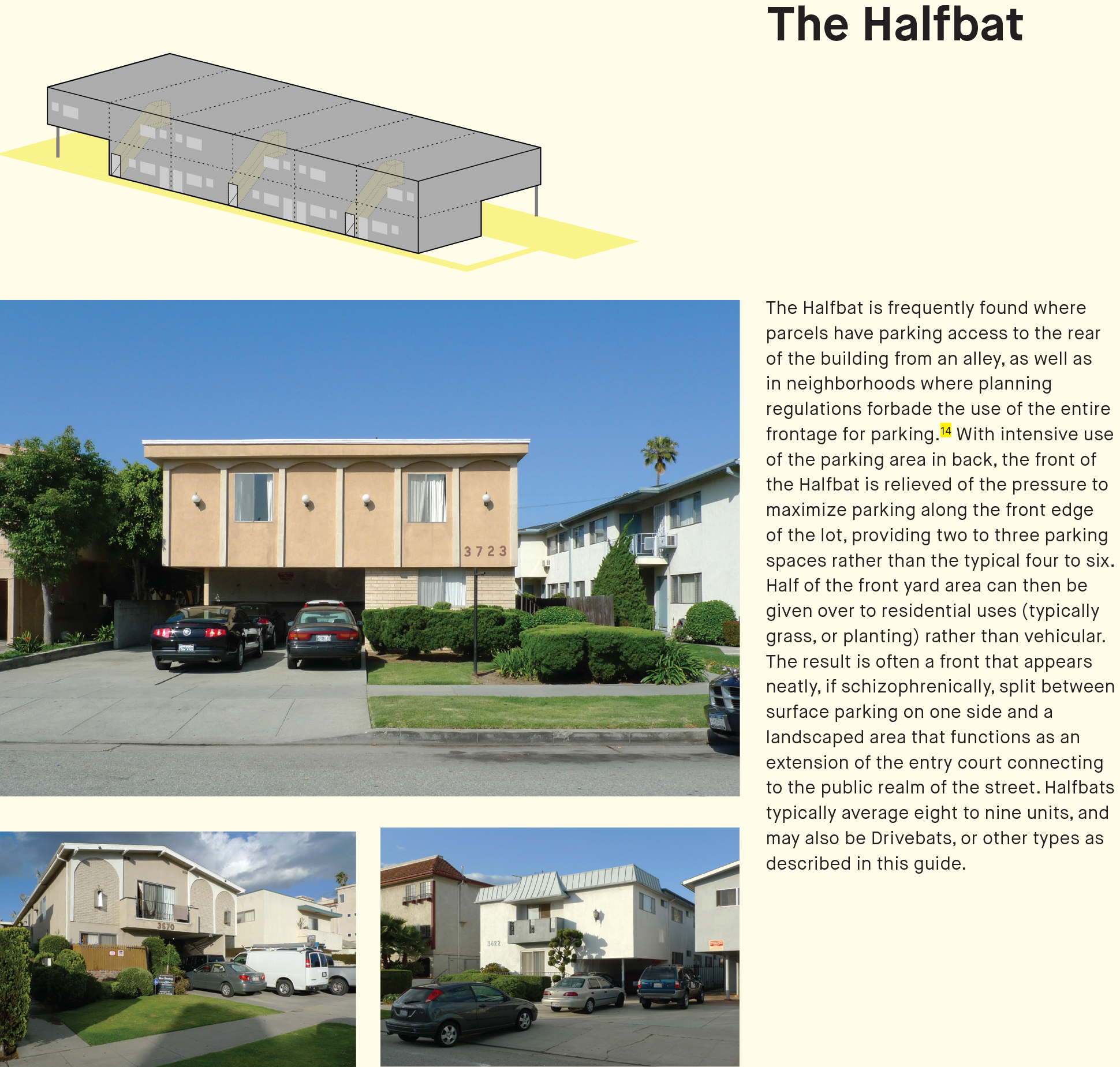

Dingbat subtypes include the Halfbat, so-named for the splitting of the front yard into areas for parking and landscape. The Halfbat emerged largely through regulations developed in response to the endless concrete wastelands created when dingbats were built across several adjacent lots [”Field Guide to Dingbats,” James Black and Thurman Grant].

Dingbat subtypes include the Halfbat, so-named for the splitting of the front yard into areas for parking and landscape. The Halfbat emerged largely through regulations developed in response to the endless concrete wastelands created when dingbats were built across several adjacent lots [”Field Guide to Dingbats,” James Black and Thurman Grant].